The Evolution of Batting Statistics

- Michael Paul

- Dec 29, 2018

- 8 min read

Baseball statistics, and subsequently the way in which we evaluate the contributions of baseball players to their teams, have undergone many changes and innovations over the years – especially in the past decade or so.

The strides forward that the game of baseball have taken in recent years with the implementation of MLB Advanced Media’s Statcast, for example, speaks very strongly to where we are now collectively. What was once believed to be a game best evaluated using only our eyes has now become a game that is very much dissected and evaluated through an analytical lens. Every MLB team has an analytics department in their front office that they lean on heavily for cutting-edge information. The hope is that it can give them a competitive advantage, if only for a short window before another organization inevitably evens the playing field.

It was during the recording of our latest podcast episode that it dawned on me that the stats some of us use on a regular basis are not second nature to everyone. I would very much like to help familiarize you with the latest, best, and all-encompassing statistics in which to evaluate a hitter. For those of you with a moderate or extensive grasp of advanced statistics, my hope is that you’ll come away with either having learned something from this article, or that you will have at least found it informative or well-written. No matter your level of knowledge, let’s have a discussion and I encourage you to leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

I truly believe that there is so much more to the game than what you can assess with your eyes or through the most basic of statistics like batting average, home runs, and runs batted in. Baseball is a game of nuances and the seemingly smallest of contributions can ultimately play a significant role in helping to identify the game’s top players throughout the entirety of a grueling 162-game schedule. That’s a lot of baseball, friends.

Before we get to the reason we’re here, I’d like to, for mostly contextual reasons, run through a brief history of a few of the most frequently used basic batting statistics and how they helped lay the groundwork for advanced statistics. Having said that, I’m going to operate under the assumption that, if you’re reading this, you have at least some knowledge of baseball statistics, even if it’s just the basics. That’s okay!

AVG

Batting average (usually abbreviated as either AVG or BA) is a statistic that every fan or player of the game since the turn of the 20th century is likely familiar with. It’s the average performance of a batter, expressed as a ratio of a batter’s safe hits per official at-bats. For years, it was thought of as the holy grail, the most truly indicative statistic in which to measure a player’s hitting abilities. We now know that, while AVG has some merits, it’s generally a very shallow and often luck-based statistic. It is not predictive of future success, nor does it incorporate a hitter’s ability to get on base in ways other than a hit. It completely ignores the walk – which is obviously a very important aspect of batting – and the hit by pitch – which can, and often should, be considered a skill of the hitter.

Justin Smoak’s AVG in 2018 was .242, which, if evaluated through the scope of this statistic, is downright awful.

Throughout the article, I’ll continue to elaborate using Justin Smoak as an example, and you’ll eventually come to see the relevance of this.

OBP

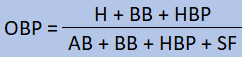

After decades of uncontested reign atop the hierarchy of baseball statistics, AVG was finally usurped by On Base Percentage (OBP). OBP is much better than AVG is at telling us how often a hitter avoids making an out, which is obviously important for a hitter. Most of you have probably either read or watched Moneyball, which highlighted the importance of not making an out. It also depicted the competitive advantage in which capitalizing on a market inefficiency, like OBP at the time, can provide a team. OBP incorporates hits, walks, and that consolatory base awarded for getting plunked with the ball (ouch!).

To the formula!

Justin Smoak’s OBP in 2018 was .350, which is comfortably above average (.318). Even though Smoak’s AVG was as low as it was, he more than made up for that unfortunate fact by safely reaching base more than his fair share. While OBP is leaps and bounds better than AVG, as evidenced by Smoak, it still pales in comparison to some of the stats we will look at momentarily. Where OBP fails is that it doesn’t assign a proper value to each outcome individually and instead all non-out events are treated equally – a walk is not distinguished from a home run, for example. That’s not the fault of on-base percentage, as that’s not what it endeavours to measure. OBP is a pretty useful stat when used appropriately and in conjunction with other stats, and it should be preferred to AVG in virtually every scenario.

SLG

Around the same time that OBP was gaining traction within the baseball community, slugging percentage (SLG) began its rise to quasi-prominence. SLG measures the total number of bases per at-bat; the higher the number, the better. For example:

In 2018, Justin Smoak had 63 singles, 34 doubles, 0 triples, and 25 home runs. To break this down a little further, that's 63 bases for the singles, 68 bases for the doubles (34 x 2), and 100 bases for the home runs (25 x 4). This is 231 bases in total, which, when divided by the 505 at bats he had, equals a slugging percentage of .457.

SLG is relevant to us because it accounts for one half of the combination-statistic known as OPS (On-base Plus Slugging), which we will come back to in a little bit. The knock against OPS is that it treats OBP and SLG as equal, but, in regards to its effect on run scoring, OBP is almost twice as important as SLG.

*****

While some people still prefer to use surface statistics like AVG, OBP, Home Runs (HR), and Runs Batted In (RBI) to measure a hitter’s overall contributions to his team, I’m of the opinion that using more advanced stats allows for a much more accurate portrayal of what happened – and, perhaps much more importantly, what is likely to happen in the future.

In recent years, the mainstream adoption of more advanced metrics such as wOBA, OPS+, and wRC+ has helped change the landscape of statistical evaluation in baseball for the better. These metrics have been proven to be more reliable year-to-year, more descriptive, and more predictive than the rate stats we just discussed – AVG, OBP, and SLG.

wOBA

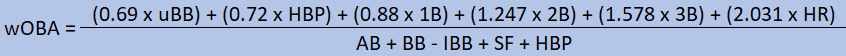

Those of you that are familiar with the sabermetric movement likely know who Tom Tango is – co-author of The Book and creator of numerous baseball stats, including wOBA (Weighted On-Base Average). For familiarity’s sake, wOBA is scaled to resemble OBP, although it’s calculated very differently. As I pointed out earlier in the article, OBP doesn’t attempt to weigh or distinguish between baseball batting events – it treats all non-outs the same, regardless of the result. wOBA attempts to do the opposite. It does a better job than AVG, OBP and SLG of calculating a hitter’s total offensive output.

We know that all ways in which to avoid making an out are not equal. A home run is worth more than a triple, double, single, walk, or hit by pitch; a triple is worth more than a single; a double is worth more than a hit by pitch; and so on. wOBA assigns each outcome a linear weight and calculates it into one easily-digestible statistic:

The league average wOBA in 2018 was .315. As I mentioned before, wOBA and OBP are scaled similarly – the league average OBP was .318. Let’s again use Justin Smoak as a comparative, since we know that he’s a pretty good hitter: Smoak’s wOBA in 2018 was .349, which was 34 points higher than league average – this is a good mark but not a great mark. This number seems to pass the sniff test based on the calibre of hitter that we know Justin Smoak is and when considering how he did at the plate in 2018 – he was good but not great.

wOBA is not park-adjusted, meaning that hitters playing in bandboxes such as Coors Field will have generally inflated wOBAs. However, the biggest knock against wOBA is that it is outperformed at the team level – in terms of reliability, descriptiveness, and predictiveness – ever-so-slightly by OPS. This was a shocking revelation when originally unveiled by Cyril Morong and it was later confirmed by Baseball Prospectus.

OPS+

Baseball-Reference’s OPS+ stat, as with all ‘plus’ stats, is put on an easily digestible scale – 100 is league average and a higher number is better (as indicated by the ‘+’). Let’s turn to ol’ Smoakie again for an example – he had a 123 OPS+ in 2018. This indicates that, according to OPS+, he was 23% better than league average as a hitter this past season. OPS+ is obviously OPS-based, but it’s adjusted for park effects and other small variables that add up to a big difference in how accurately and reliably the stat correlates to team runs, historically.

Although OPS+ is less effective than wRC+, it’s well ahead of AVG, OBP, and SLG. Yet for some reason, it’s been seemingly more widely-adopted to the mainstream than the superior wRC+. This is probably because of the familiarity that a lot of the community already have with OPS as a somewhat commonly-used statistic in television broadcasts.

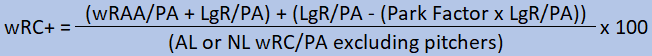

wRC+

wRC+, or Weighted Runs Created Plus (uses the same scale as OPS+ and other ‘plus’ stats), has, over the past few years, become the preferred hitting statistic of sabermetricians and staunch supporters of advanced statistics everywhere, and rightfully so. It correlates more tightly to team runs/PA than any other publicly-available statistic. It’s also complex in nature, although I say that with great admiration.

From FanGraphs’ Glossary:

Weighted Runs Created Plus (wRC+) is a rate statistic which attempts to credit a hitter for the value of each outcome (single, double, etc.) rather than treating all hits or times on base equally, while also controlling for park effects and the current run environment. wRC+ is scaled so that league average is 100 each year and every point above or below is equal to one percentage point better or worse than league average. This makes wRC+ a better representation of offensive value than batting average, RBI, OPS, or wOBA.

And here’s how it's calculated:

To provide a little bit of backstory, wRC+ is an adjusted and scaled version of Tom Tango’s wRC (Weighted Runs Created), which is an improved version of Bill James’ Runs Created (RC) statistic. Per FanGraphs, RC attempted to quantify a player’s total offensive output and measure it by runs. While the idea was sound, James’ idea has since been replaced with Tango’s wRC. wRAA, seen in the calculation of wRC+ above, is essentially just wRC with league average scaled to zero. LgR/PA is League Runs per Plate Appearance, which is the total number of runs scored divided by the total number of plate appearances in MLB during that season. The Park Factor for all previous seasons can be found here.

As previously mentioned, wRC+ works on a scale where 100 represents league average. So even if you don’t quite grasp how it’s calculated, it’s constructed to be incredibly easy to use and understand. Let’s look at good guy Smoak again for an example of wRC+ in action.

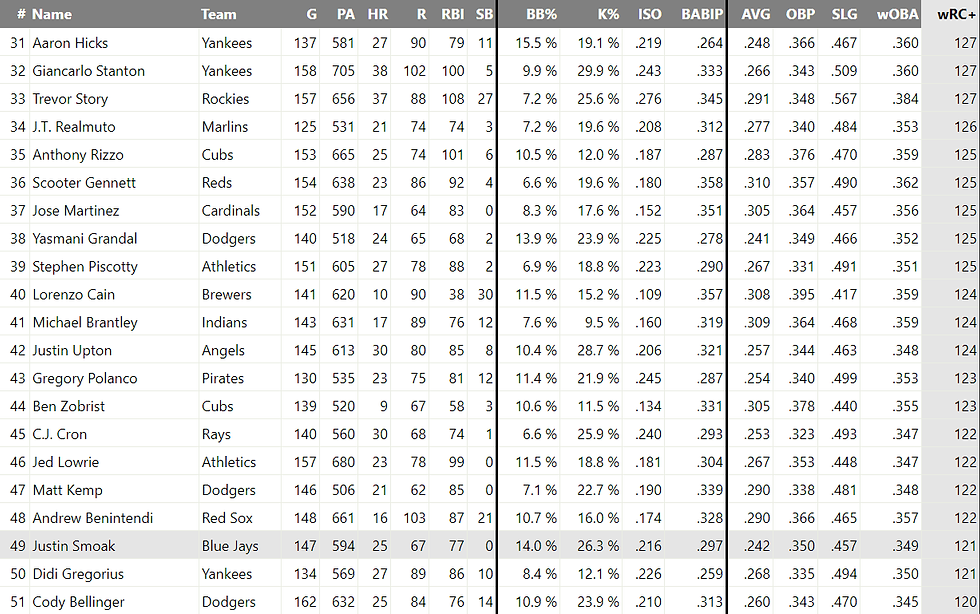

Over the meadow and through the woods, to the Fangraphs graphic we go:

Smoak’s wRC+ in 2018 was 121, indicating that he was 21 percent better than a league average hitter this past season. It was also the 49th-best mark in all of baseball among qualified hitters, sandwiched between Andrew Benintendi’s 122 and Cody Bellinger’s 120. Smoak is good at smashing baseballs! We already knew this, but a statistic like wRC+ helps capture Smoak’s true total offensive output that a stat like batting average – or even a combo of AVG, HR, and RBI – fails to do. Sincerely, that is an example of one of the biggest benefits to using sabermetrics to evaluate baseball.

When looking at Justin Smoak’s surface stats - .242 AVG/.350 OBP/.457 SLG/25 HR/77 RBI, I feel like it would be easy to overlook the positive contributions that Justin Smoak made to the Blue Jays from the plate in 2018. This was not an article about Justin Smoak, but I did indeed use Smoak as a recurring example to highlight the disparity between basic and advanced statistics. And now that we’ve taken more than just a fleeting glance at some of the most-used advanced statistics in baseball, I’m hopeful that this article has proven to be helpful to you in some way, shape, or form.

Keep your eyes peeled for an upcoming article that will dive into Baseball Prospectus’ new batting metric, DRC+.

Thanks for reading The Evolution of Statistics by Michael Paul. If you have any questions or comments relating to this article, we encourage you to leave them below. For all general inquiries, we can be reached at the following:

Twitter https://twitter.com/radio_scouts

Comments